The game was developed by Anastasia Rychkova, a student at ITMO’s Faculty of Software Engineering and Computer System. Even though she had no background in chemistry, she completed the project and made it available for the first users. The results of the work were published in the Journal of Chemical Education.

VR and Chemistry

Some topics are always challenging for students no matter how hard a professor tries to explain them. Every subject has such tough spots and it has nothing to do with the level of the lecturer's expertise. That's why it's especially crucial to come up with new ways of presenting such materials.

As noted by Mikhail Kurushkin, dean of the Faculty of Biotechnologies and leading research associate of the ChemBio Cluster, understanding the electronic structure of an atom is extremely difficult for students. In 2016, he even developed a board game in the spirit of the old-school Battleship game to playfully encourage students to study the topic.

Mikhail Kurushkin

In 2018, Mikhail and his university colleagues wanted to create a project to study the role of virtual reality in chemistry education at universities. That's when he remembered his previous attempt and decided to give it another shot but in a new format.

"We came up with an idea to transfer this board game into virtual reality," recalls Mikhail Kurushkin. "The introduction of the VR technologies that automatically control what students have learned can assist professors in teaching the electronic structure of an atom to a large number of students at the same time."

Lanthanides vs actinides

VR Chemistry game. Illustration from the article. Credit: pubs.acs.org

In order to become an efficient learning tool, the game should be able to impress students. That's why the team of creators had to think of a creative way to present it.

"I proposed to set the Battleship game in outer space. So that the players would be spaceship captains of different alien races in the state of war. I wanted to call the races lanthanides and actinides and Mikhail really liked the idea. So we not only came up with visual content but also added some storytelling to maximize the effect," says Artem Smolin, head of the Center of Usability and Mixed Reality and associate professor at ITMO’s Faculty of Software Engineering and Computer Systems.

Artem Smolin

Anastasia Rychkova, a third-year Bachelor’s student of the Computer Technologies in Design program, was in charge of coding. She had to find a way to transfer the idea of space battles based on chemical objects and phenomena to virtual reality.

"We started by studying the engine and for a while, I have been trying to figure out a way to do it. The problem was that at that time the VR Oculus Go headsets that we used were brand-new and there was little information available. We had to use the trial and error method," she says. "Then designer Alexey Korotkikh joined our team and we started to work on the project itself. It was like playing Minesweeper. The biggest "explosion" happened in November. The game was almost ready but then the engine was updated and some of the functions disappeared. So, we had to search for an alternative."

Anastasia Rychkova. Photo courtesy of the subject.

One of the biggest problems was creating a player vs player mode. Anton Smolin notes that it came as a surprise that there is no multiplayer feature in VR. But Anastasia Rychkova managed to solve this problem by creating a dedicated server.

"At first we had two headsets working autonomously and we had to create a separate program. However, as a result, we even won in this situation as now all headsets could connect to one device," she says.

Calling “shots” at quantum numbers

VR Chemistry game. Illustration from the article. Credit: pubs.acs.org

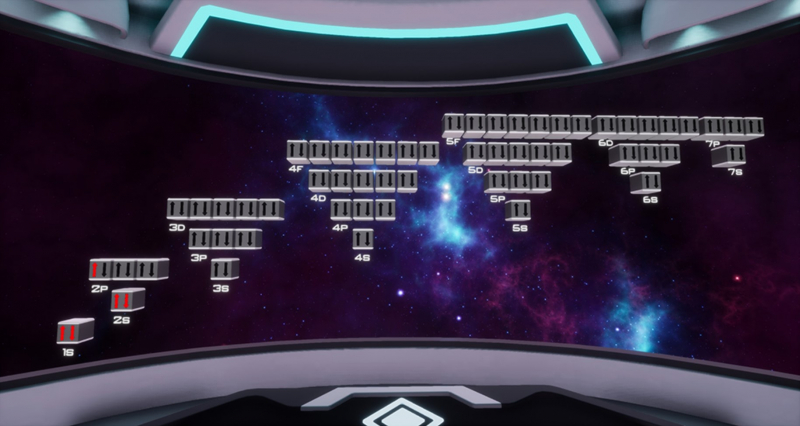

The game still has the basic principles of the Battleship game. The players are to destroy the enemy fleets before their ships get destroyed. Only instead of the number and letter coordinates, the protagonist must attack containers with arrows, which represent the state of electrons in an atom.

"The enemy fleet in the form of containers is hanging in front of you in space, and you need to shoot at it with a laser," explains Mikhail Kurushkin. "The coordinates are quantum numbers that describe the state of an electron in an atom. Basically, you need to understand how electrons are distributed across orbital diagrams to play well."

Before each round, the players guess a chemical element, and then, using the diagram from the containers, they start to guess the enemy's element.

"You can follow one of two strategies: you either shoot to the very end and name a chemical element when you are absolutely sure of it," explains Artem Smolin, "or take a risk. In this case, you take a close shot, see a certain range of possible elements, and name the element. If you guess wrong – you lost, if you guess right – you won. Since excitement comes into play here, the game ultimately helps to memorize the information."

VR Chemistry game. Illustration from the article. Credit: pubs.acs.org

Despite the pandemic

The game was almost finished earlier this year. In February, the first prototype of the game was presented at ITMO Open Science and it helped to reveal a number of inaccuracies that required some improvement.

"In February, we piloted our game and learned what difficulties people may face," Anastasia Rychkova recalls. "People often had problems due to their lack of background in chemistry and when the professor wanted to help, they had to take off VR headsets and then put it on again. To avoid it, we needed to create a kind of a monitoring tool so that the professor could see what is happening in the students' VR headsets. Then the pandemic began and I had the opportunity to finalize the game and fix the remaining bugs. By June, we were able to test out our brainchild."

ITMO Open Science 2020

In order to demonstrate its efficiency, Nadezhda Maksimenko, one of the key project participants from the Chemistry Neuroeducation laboratory, conducted an experiment with ITMO University students.

The results of the work were published in the Journal of Chemical Education. The article includes the game’s description and information on how to download it. Next year, the creators intend to make an online version of the orbital Battleship.

Source https://news.itmo.ru/en/education/trend/news/9799/